The Evolution of Real-World Assets (RWA): From E-Gold to Institutional Tokenization

The architecture of tokenized real-world assets (RWA) has been rebuilt from scratch five times in thirty years. Each rebuild solved the previous generation’s critical engineering failure and introduced a new category of trade-off. This article traces the technical evolution, from centralized ledgers to compliance-embedded smart contracts, examining what each architecture got right, what it got wrong, and why the next generation had to exist.

Era 1: How E-Gold Built the First Digital Asset Ledger (1996 to 2008)

Overview

E-Gold, founded in 1996 by Douglas Jackson and Barry Downey, was the first widely adopted digital gold currency. It operated on a centralized infrastructure years before blockchain existed. The system stands as the conceptual ancestor of every tokenized asset system that followed, not because of its technology, but because of its ambition: instant peer-to-peer settlement of value backed by a tangible asset, without banking intermediaries.

At its peak, E-Gold reportedly processed over $6 million in daily transaction volume. But the centralized architecture that enabled this speed also created a fatal single point of failure. When U.S. regulators expanded money transmission laws post-2006, E-Gold had no defense. The founders were indicted in 2007, and the system shut down in 2008.

Technical Architecture

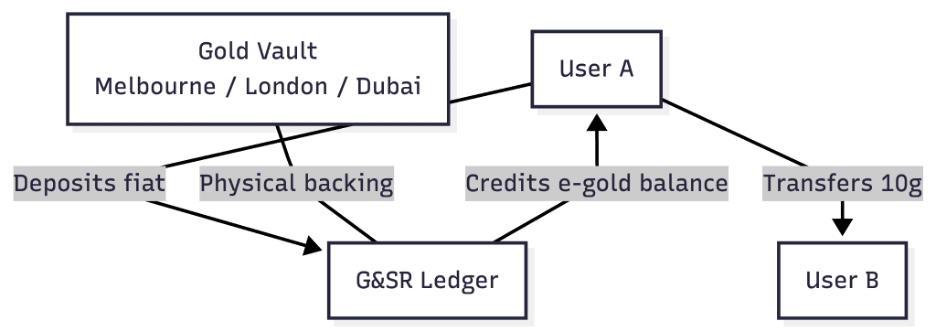

Architecture: Centralized SQL-style database operated by Gold & Silver Reserve Inc. (G&SR), the company behind E-Gold.

Core components:

- Centralized Ledger: A traditional database on G&SR servers stored all balances, transaction history, and credentials. A single source of truth controlled by one company.

- Exchange Mechanism: Registered exchangers converted fiat to e-gold units, crediting user accounts after accepting bank transfers or credit card payments.

- Cryptographic Signing: Transactions were digitally signed so only the account holder could authorize transfers.

Transaction flow: User A deposits $1,000 via bank transfer. G&SR converts it to 25 grams of e-gold at market price, crediting User A’s account. User A transfers 10 grams to User B via the web interface. The ledger updates instantly: A decreases by 10g, B increases by 10g. No clearing house, no multi-day delay, no third-party approval. Once confirmed, transactions could not be reversed, achieving finality in seconds rather than the T+1 to T+3 clearing cycles of traditional banking.

Irreversible settlement was a defining design choice of this era. In 1996, the idea that a digital payment should be final, with no chargebacks and no reversal window, was radical. Credit card networks and PayPal built their business models around reversibility. E-Gold rejected that premise, implementing finality through a centralized database. Over a decade later, Bitcoin would arrive at the same property through proof-of-work consensus, removing the need for a trusted central party entirely. The architectural approaches were different, but the core principle was shared: settlement should be final. As Satoshi Nakamoto noted in 2009, the lesson from earlier digital currencies like E-Gold was not about settlement design but about centralization: “I hope it’s obvious it was only the centrally controlled nature of those systems that doomed them.”

Impact

- The Financial Times described it as “the only electronic currency that has achieved critical mass on the web” (1999)

- Grew to 5 million accounts, processing over $2 billion in annual transactions at its peak

- Demonstrated fractional ownership: users could hold as little as 1 gram of gold (~$40)

The system was founded by a radiation oncologist and an attorney, operating from Melbourne, Florida, with no venture capital backing. It reached millions of users through word-of-mouth and web forums. That demand signal, for instant, low-fee, borderless asset transfer, has driven every subsequent era of tokenization. The demand existed; E-Gold was the wrong architecture for delivering it.

What It Got Wrong

- Single point of failure: One company, one jurisdiction, one database. When G&SR was targeted by regulators, the entire network died.

- No programmability: The system could transfer value and nothing else. No conditional logic, no automated distributions, no smart contracts.

- Centralized price oracle: G&SR’s own pricing algorithm determined the gold price; there was no market consensus mechanism.

- No secondary market: All transactions had to flow through G&SR’s ledger. Users could not trade peer-to-peer outside the platform.

The single point of failure was the fatal flaw, and every subsequent era of tokenization can be read as an attempt to distribute that single point across a network. Thirty years later, custody and identity verification still remain concentrated with individual entities. The point of failure moved, but it never disappeared.

Era 2: How Colored Coins Tokenized Assets on Bitcoin (2012 to 2015)

Overview

E-Gold’s collapse proved that centralized digital asset systems could not survive regulatory pressure. The next generation of builders drew an obvious conclusion: the ledger itself had to be decentralized. Colored Coins represent the first attempt to move asset tokenization from centralized servers onto a decentralized blockchain.

The concept originated in a March 2012 blog post by Yoni Assia (CEO of eToro), was formalized by Meni Rosenfeld’s whitepaper later that year, and further developed in a 2013 whitepaper co-authored by Assia, Rosenfeld, and a then-19-year-old Vitalik Buterin. The project never achieved mainstream adoption, but its influence was enormous. Tether, launched on the Omni Layer in 2014, became the most successful descendant of this era, proving that blockchain-based tokenized currency could achieve a $100B+ market cap.

Technical Architecture

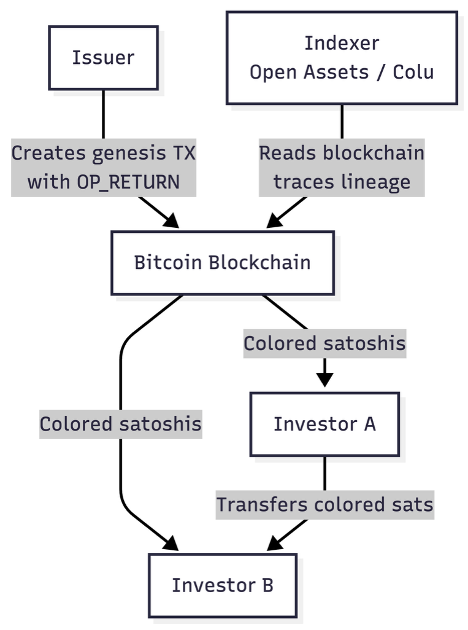

Architecture: Metadata layer on top of the Bitcoin blockchain (no protocol-level changes required).

Core components:

- UTXO Tracking: Bitcoin’s Unspent Transaction Output model allowed specific outputs to be “colored.” By tracing which outputs descended from a genesis transaction, wallets could determine asset ownership without modifying Bitcoin’s core logic.

- OP_RETURN Field: Bitcoin transactions can embed up to 40-80 bytes of arbitrary data. This became the primary on-chain storage for asset metadata, encoding asset name, total supply, and transfer rules.

- Coloring Protocol / Indexers: Specialized wallet software and secondary indexers (Colu, ChromaWallet, Open Assets Protocol) tracked the chain of ownership transfers for colored satoshis.

Transaction flow: A stock issuer creates a genesis transaction with OP_RETURN data encoding asset metadata. This output becomes the canonical color source. The issuer transfers colored satoshis to investor addresses (e.g., 100 satoshis = 100 shares). Colored Coins indexers observe the Bitcoin blockchain and trace satoshi lineage back to genesis, crediting investors with share ownership. Any participant can download the ledger and verify the entire chain of title by replaying transactions.

The architectural approach of building on top of Bitcoin without modifying the base protocol was also the system’s deepest constraint. Every implementation team ended up building a proprietary indexer layer. The “decentralized” asset system required a centralized interpretation layer to function. This tension between base-layer neutrality and application-layer specialization persists in every RWA system built since.

Impact

- Proved decentralized asset tokenization was technically feasible without modifying the base blockchain

- Spawned Tether/Omni Layer, now the dominant stablecoin infrastructure

- Established the conceptual foundation for all modern token standards (ERC-20, ERC-721)

The most consequential outcome of the Colored Coins era was not any product it shipped but the developer it frustrated. Buterin’s experience attempting to build programmable asset logic on Bitcoin’s limited scripting language became one of the most consequential engineering dead ends in technology history.

As Buterin later explained:

“I was working on Mastercoin and colored coins back in 2013; after a few weeks working on the projects I realized how the approach of trying to target a specific set of use cases was too limited.”

Without that dead end, there would be no Ethereum, no ERC-20, no DeFi, and no $9B tokenized Treasury market.

What It Got Wrong

- No smart contracts: Colored Coins only supported value transfer. There was no way to automate dividend payments, enforce conditions, or implement derivative logic.

- Bitcoin throughput constraints: ~7 transactions per second meant colored transactions competed with regular Bitcoin for scarce block space, and fees could spike to $5-100+ during congestion.

- Fragmented ecosystem: Multiple competing implementations (Open Assets, EPOBC, Colu) created wallet incompatibility and developer confusion. No single standard emerged.

- No oracle mechanism: There was no built-in way for on-chain tokens to know the real-world asset’s current value. Projects relied on external feeds or trusted third parties, reintroducing centralization.

The fragmented ecosystem was the most damaging failure of this era. If Colored Coins had coalesced around a single standard the way ERC-20 later did, Bitcoin might have become the programmable asset platform that Ethereum became. Standards convergence, not raw technical capability, is what determines platform adoption. This lesson repeats itself in Era 5, where ERC-3643 and ERC-1400 compete for the same role.

Era 3: Ethereum and ERC-20 Bring Programmable Tokenization (2015 to 2020)

Overview

Buterin’s frustration with Bitcoin’s scripting limitations while building Colored Coins tools led directly to Ethereum’s design. Where Bitcoin offered a narrow scripting language sufficient for value transfer, Ethereum offered a Turing-complete virtual machine capable of running arbitrary programs. This was not an incremental improvement; it was a categorical leap.

Ethereum’s launch in July 2015 transformed asset tokenization from metadata annotation into programmable, condition-triggered execution. The ERC-20 token standard, proposed in 2015 and widely adopted by 2017, gave fungible tokens a unified interface. Any wallet, exchange, or DeFi protocol could support new tokens without custom integration.

This era marked the moment tokenization became composable. ERC-20 tokens could serve as collateral in lending protocols, trade on decentralized exchanges, and trigger automated dividend distributions, all without manual intervention. The ICO boom of 2017-2018, which raised an estimated $20 billion through ERC-20 tokens, stress-tested the infrastructure and attracted millions of developers. ERC-721 (2018) later enabled the representation of unique assets for non-fungible items. Early DeFi platforms like MakerDAO (now rebranded as Sky) and Uniswap proved that tokenized assets could function as programmable collateral within autonomous protocols.

Technical Architecture

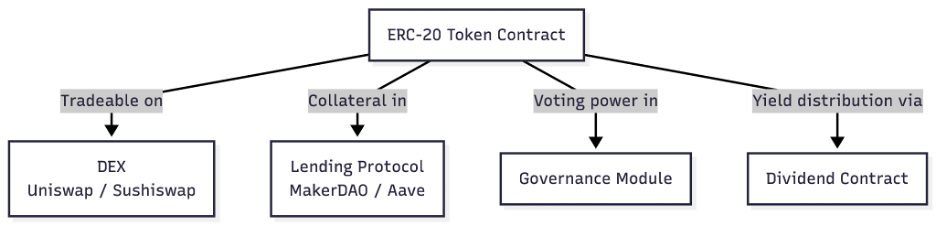

Architecture: Smart contracts on the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM).

Core components:

- Solidity Smart Contracts: Turing-complete bytecode executed on every Ethereum node, enabling arbitrary business logic for asset issuance, transfer, and governance.

- ERC-20 Standard Interface: A predefined set of functions all compliant tokens must implement: transfer(), balanceOf(), approve(), transferFrom(), totalSupply(). Events: Transfer, Approval.

- Gas System: Execution cost measured in “gas” and paid by the transaction sender, incentivizing validators and preventing infinite loops.

- Composability Layer: Tokens could interact with other smart contracts (DEXs, lending pools, governance modules) without permission or custom integration.

Transaction flow (real estate example): A property owner deploys an ERC-20 contract that represents a building, with 100M tokens. An investor sends 1 ETH; the contract calculates and mints 10,000 tokens. The property manager collects rental income, converts it to USDC, and sends it to the contract. The contract executes automated proportional distribution to all token holders. An investor sells 5,000 tokens on Uniswap; the DEX contract handles the atomic swap. Settlement completes in 12-15 seconds.

The transformative element of this architecture was the composability layer. In Eras 1 and 2, assets lived in silos: E-Gold balances could not interact with anything outside G&SR’s database, and Colored Coins could not trigger conditional logic. ERC-20 tokens, by contrast, were building blocks that any protocol could plug into. This composability is what created DeFi as a category, and it remains the single most important architectural contribution of the Ethereum era.

Impact

- ERC-20 became the universal token standard with hundreds of billions in tokens created across the ecosystem

- MakerDAO accepted real-world assets as collateral to back DAI, eventually reaching $4.6B in U.S. Treasury exposure as the protocol expanded its RWA strategy

- Fractional ownership became accessible to retail investors at $50 minimums

- DeFi composability proved that tokens could serve as building blocks across protocols

The ERC-20 standard itself was unremarkable in isolation (a handful of function signatures), but the interoperability it unlocked was extraordinary. Every new token launched was immediately tradable on every DEX, usable as collateral in all lending protocols, and visible in all wallets. That network effect is what the Colored Coins era lacked, and it is what made Ethereum the default platform for tokenized assets.

What It Got Wrong

- No built-in compliance: ERC-20 has zero KYC/AML, investor accreditation, or transfer restriction capabilities. Any address can buy or sell. This made institutional adoption impossible.

- Gas fee spikes: During network congestion, transaction fees reached $5-100+, making small fractional ownership transactions economically impractical.

- Oracle dependency unresolved: Real estate or commodity token values still depended on external price feeds with no decentralized consensus on “true” asset value.

- Off-chain custody gap: Smart contracts cannot enforce real-world lease agreements or seize physical property. The underlying asset always required a trusted off-chain custodian, preserving counterparty risk.

- No structured finance primitives: ERC-20 tokens are flat; they have no concept of tranching, seniority, or risk stratification. Traditional asset managers had no way to model securitization structures on-chain.

The absence of on-chain compliance mechanisms was the primary barrier to institutional adoption. Gas fees can be optimized, and oracles can be improved, but the lack of any on-chain mechanism to restrict who can hold a token was a categorical disqualifier for regulated capital. Institutional money that remained on the sidelines during 2017-2020 was waiting for the compliance layer that Era 5 would provide.

Era 4: Centrifuge and the Rise of Structured DeFi Credit Pools (2020 to 2022)

Overview

Ethereum’s ERC-20 standard proved that tokenization could be programmable and composable, but it offered no mechanism for tranching, risk stratification, or structured credit. Traditional asset managers looked at flat ERC-20 tokens and saw no way to model the securitization structures they had used for decades. Centrifuge was built to fill that gap.

Launched in 2017 with significant traction from 2020 onward, Centrifuge introduced structured RWA pools organized into tranches, a mechanism borrowed from traditional finance’s securitization playbook and adapted for DeFi. The Tinlake platform allowed asset originators to pool tokenized RWAs and issue two tranches: senior DROP tokens (lower yield, first to be repaid) and junior TIN tokens (higher yield, absorbs losses first). This replicated how traditional CLOs and mortgage-backed securities already worked, executed transparently on-chain. Its integration with MakerDAO, where DROP tokens served as collateral for DAI issuance, proved that non-speculative, credit-based real-world assets could sustainably back DeFi stablecoins.

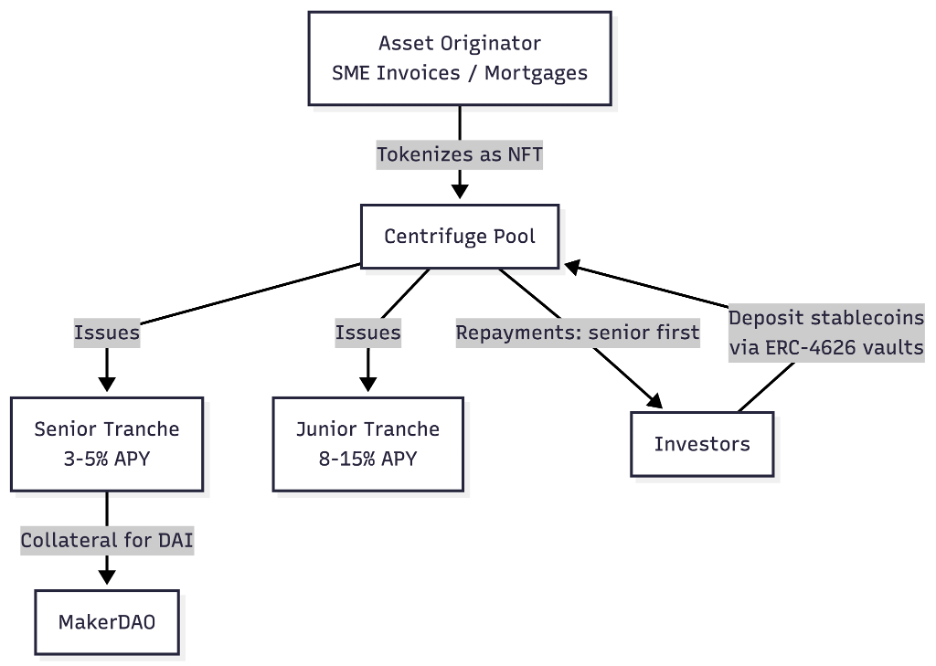

Technical Architecture

Architecture: Centrifuge initially launched on a Substrate-based chain with Tinlake smart contracts on Ethereum. In 2025, it migrated to a fully EVM-native architecture (Centrifuge V3), deprecating Substrate and Tinlake in favor of multichain ERC-4626 vaults. The current architecture is described below.

Core components:

- EVM-Native Pools: Smart contracts deployed directly on Ethereum and L2 chains, eliminating the bridge risk of the earlier dual-chain design.

- ERC-4626 Vaults: Standardized tokenized vault interface for deposits, withdrawals, and yield accounting, replacing the earlier Tinlake pool contracts.

- NFT + Legal Wrapper: Each invoice or mortgage is converted to an on-chain NFT with the off-chain legal document linked via cryptographic hash. This pairing anchors the real-world contract to its on-chain representation.

- Tranche Mechanism:

- Senior Tranche: ~3-5% APY; first claim on repayments; lower risk.

- Junior Tranche: ~8-15% APY; absorbs losses; higher risk.

Transaction flow (invoice financing): An SME with $100,000 in outstanding invoices uploads them to Centrifuge with off-chain legal agreements. A smart contract issues an NFT that represents the invoice pool. The SME opens a pool with senior ($80,000) and junior ($20,000) tranches. DeFi investors deposit stablecoins into the pool via ERC-4626 vaults; the pool mints tranche tokens accordingly. As the SME’s customers pay invoices over 30-90 days, the smart contract distributes proceeds: senior holders receive priority repayment, junior holders receive the remainder.

DeFi integration: MakerDAO accepted Centrifuge senior tranche tokens as collateral in its DAI Stability Module, with $200M+ in DAI backed by real-world credit assets by 2022. This was the first large-scale fusion of traditional credit and DeFi lending.

Impact

- Proved structured finance (tranching, risk stratification) could work transparently on-chain

- $1B+ TVL and over $500 million in assets financed across invoices, real estate, and trade finance

- Enabled MakerDAO to earn approximately 80% of its fee revenue from real-world assets

- Created new credit channels for SMEs that lacked access to traditional bank lending

The Centrifuge-MakerDAO integration stands as the most important proof point for RWA tokenization before BlackRock’s entry. It demonstrated that DeFi protocols could generate sustainable yield from real economic activity rather than circular token emissions. MakerDAO’s RWA revenue became the primary credibility signal for institutional observers evaluating on-chain asset tokenization prior to 2023.

What It Got Wrong

- Credit risk persists: Tokenization does not eliminate default risk. If an SME fails to pay invoices, token holders absorb losses regardless of the on-chain infrastructure.

- Oracle dependency for NAV: Net asset value calculations depended on real-world data feeds (invoice collection rates, property valuations). Incorrect data could cascade into mispriced tranches.

- Thin secondary markets: Despite DEX integration, DROP/TIN liquidity remained shallow. Large positions faced slippage exceeding 0.5%.

- No embedded compliance: Centrifuge pools lacked on-chain KYC/AML enforcement. Institutional capital, which requires compliance-first architecture, stayed on the sidelines.

- Off-chain custody gap continued: Underlying assets (invoices, property deeds) were still held off-chain by issuers. If an originator defaulted, recovery was a legal process, not a smart contract execution.

The most underappreciated failure of this era was the DeFi community’s treatment of credit risk. A widespread assumption held that putting invoices on-chain somehow reduced the probability of default. It did not. Tokenization improved transparency and settlement efficiency, but the underlying borrower’s ability to repay was unchanged. The DeFi ecosystem had spent years reasoning about smart contract risk and protocol risk but had limited experience modeling traditional credit risk. That gap led to several pool defaults that conventional underwriting frameworks would have flagged earlier.

Era 5: Compliance-Embedded Tokens and Institutional Entry (2023 to Present)

Overview

Centrifuge proved that structured credit could work on-chain, but its lack of embedded compliance kept institutional capital on the sidelines. The lesson was clear: for regulated capital to flow into tokenized assets, compliance could not be an afterthought bolted on top of permissionless infrastructure. It had to be woven into the token itself.

The emergence of compliance-embedded token standards, specifically ERC-1400 and ERC-3643 (T-REX, which stands for Token for Regulated EXchanges), marked a fundamental shift from crypto-native to TradFi-native RWA infrastructure. These standards embed transfer restrictions, identity verification, and document management directly into the token’s smart contract. Before any transfer executes, on-chain checks verify the receiver’s identity and regulatory eligibility.

This era provided institutional capital with a credible on-ramp. BlackRock’s BUIDL fund, launched in March 2024 via Securitize, and Ondo Finance, with its tokenized Treasury product (OUSG), became the headline entrants. The infrastructure layer matured in parallel: institutional custody from Fidelity and BNY Mellon, oracle feeds from Chainlink, real-time tracking via RWA.xyz, and regulated transfer agents like Securitize became standard components.

Technical Architecture

Architecture: Compliance-embedded token standards + institutional custody + on-chain identity registry.

Core components:

- ERC-1400 (Partially Fungible Token Standard):

- Partition-based structure: tokens grouped into partitions with metadata (regulatory status, document references).

- Document management: issuers attach legal documents with cryptographic hashes via setDocument().

- Transfer hooks: pre-transfer validation checks enforce issuer-defined rules via canTransferFrom().

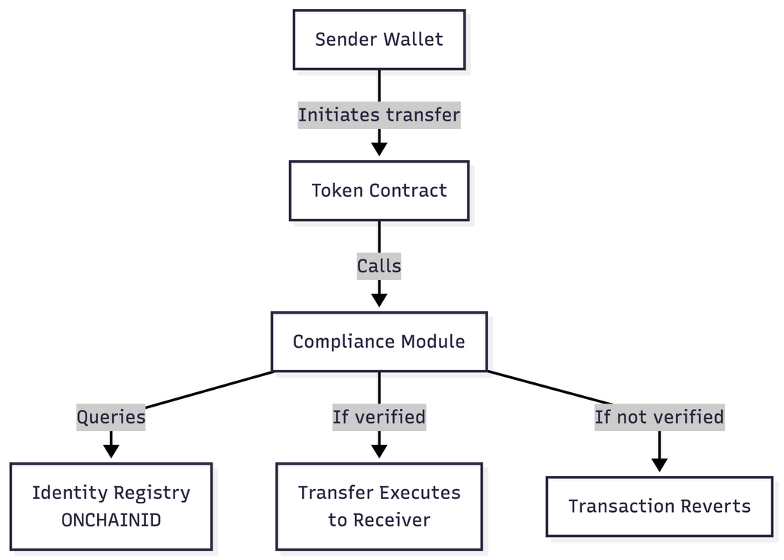

- ERC-3643 (T-REX Standard):

- Identity-centric design: every token holder linked to an ONCHAINID smart contract storing verified claims (KYC status, accreditation level, country, sanctions check).

- Modular Compliance Module: a rules engine checking holder eligibility before every transfer. If the check fails, the transaction reverts.

- Transfer flow: sender initiates transfer; smart contract calls Compliance Module; module queries Identity Registry; if approved, transfer executes; otherwise, transaction reverts.

- Institutional Fund Structure:

- Fund contract (ERC-20 or ERC-1400 base) with professional custody (Fidelity, BNY Mellon, Securitize).

- Daily NAV calculation pulled via oracle (Chainlink, Pyth).

- Automated dividend distribution via smart contract.

- Identity Registry: Maps ONCHAINID contracts to verified investor profiles. Only a cryptographic commitment to KYC data lives on-chain; full identity data is held off-chain for privacy.

- Multi-chain Deployment: Same token and compliance logic deployed across Ethereum, Solana, Arbitrum, Polygon, Avalanche, and others, with cross-chain bridges (including Chainlink CCIP) enabling asset movement.

Transaction flow (BlackRock BUIDL): An investor completes KYC with Securitize, which issues a verified claim to the investor’s ONCHAINID. The investor sends USDC to the BUIDL smart contract. The contract queries the Securitize compliance module: “Is this wallet in the approved registry?” If yes, it mints BUIDL tokens. USDC flows to the custodian (Fidelity), which purchases short-term U.S. Treasury bills. The custodian calculates daily accrued interest and reports it to an oracle. The BUIDL contract triggers daily dividend distribution proportional to each holder’s balance. When the investor transfers tokens to another investor, the contract checks the receiver’s identity before approving the transfer. Redemption burns tokens and triggers an off-chain settlement with the custodian.

ERC-3643’s identity-centric design, where compliance logic orbits around verified identity claims, maps more naturally to how regulators approach securities law, since regulators focus on who holds the asset rather than how the asset is partitioned. ERC-1400’s partition-based approach offers more flexibility for complex instrument structures, but that flexibility introduces additional complexity for compliance officers who need deterministic, auditable rule enforcement.

Impact

- Tokenized U.S. Treasuries grew from ~$0 (2022) to $9B+ (late 2025) per xyz

- BlackRock BUIDL reached $2.5B+ AUM and expanded to nine blockchains

- Ondo Finance became the largest tokenized Treasury and stock provider

- ERC-3643 adopted as a compliance standard with $32B+ in assets tokenized via Tokeny

- 24/7 settlement and daily yield accrual became operational for institutional capital

The pace of institutional adoption exceeded most market forecasts. Both BUIDL and the broader tokenized Treasury market reached a billion-dollar scale within two years of the first compliance-embedded tokens launching. This trajectory suggests that institutional demand for on-chain settlement was not the bottleneck; compliance infrastructure was. Once the compliance layer was in place, capital moved rapidly.

What It Got Wrong

- Custody remains centralized: Despite on-chain tokenization, underlying assets sit with professional custodians. If a custodian fails, token holders bear the loss. For the third consecutive era, custody remains the unsolved problem.

- Identity registry centralization: While identity claims are stored on-chain, the actual verification (KYC/AML) is performed by centralized providers like Securitize. This reintroduces a trusted intermediary.

- Cross-chain bridge risk: Multi-chain deployment requires bridges. Bridge exploits and bugs remain a significant attack surface for asset loss.

- Off-chain settlement lag: Token transfers settle instantly on-chain, but underlying asset settlement still follows traditional timelines (T+1 for Treasuries, T+2 for stocks).

- Decentralization traded away: The current institutional RWA architecture is traditional finance re-platformed on blockchain. Custody, identity, and issuance are all centralized; only the transfer layer is decentralized. This is faster TradFi, not a new paradigm.

Centralization of the identity registry is the most consequential limitation on the long-term trajectory of this space. Custody centralization is a known, accepted trade-off with well-established legal frameworks. But identity centralization means that a single provider (Securitize, for BUIDL) holds the keys to who can and cannot participate in the tokenized asset market. If zero-knowledge proof systems and decentralized identity frameworks (such as W3C Decentralized Identifiers and verifiable credentials) mature enough to enable compliance verification without centralized identity registries, that would represent a genuine architectural breakthrough. Until then, Era 5 has swapped one gatekeeper (the bank) for another (the identity provider).

Conclusion

Across five eras, each generation of RWA tokenization solved the previous generation’s failures by adding a layer of abstraction: metadata over centralized databases, smart contracts over metadata, tranching over flat tokens, compliance modules over permissionless contracts. The persistent trade-off has been between decentralization and institutional viability, and the current era resolved it by accepting recentralization at the custody and identity layers. Today, the distributed ledger serves as the transfer rail, not the trust layer. Whether the next generation of infrastructure, zero-knowledge proofs, decentralized identity, cross-chain interoperability via Chainlink CCIP, and Layer-2 scaling can shift that balance remains the defining open question. Each era’s solution became the next era’s constraint, and that pattern shows no sign of ending.